Prisoner of the Robots

Dimension: SfaD

Author: Peter Matthew Check

Date: February 2, 2021

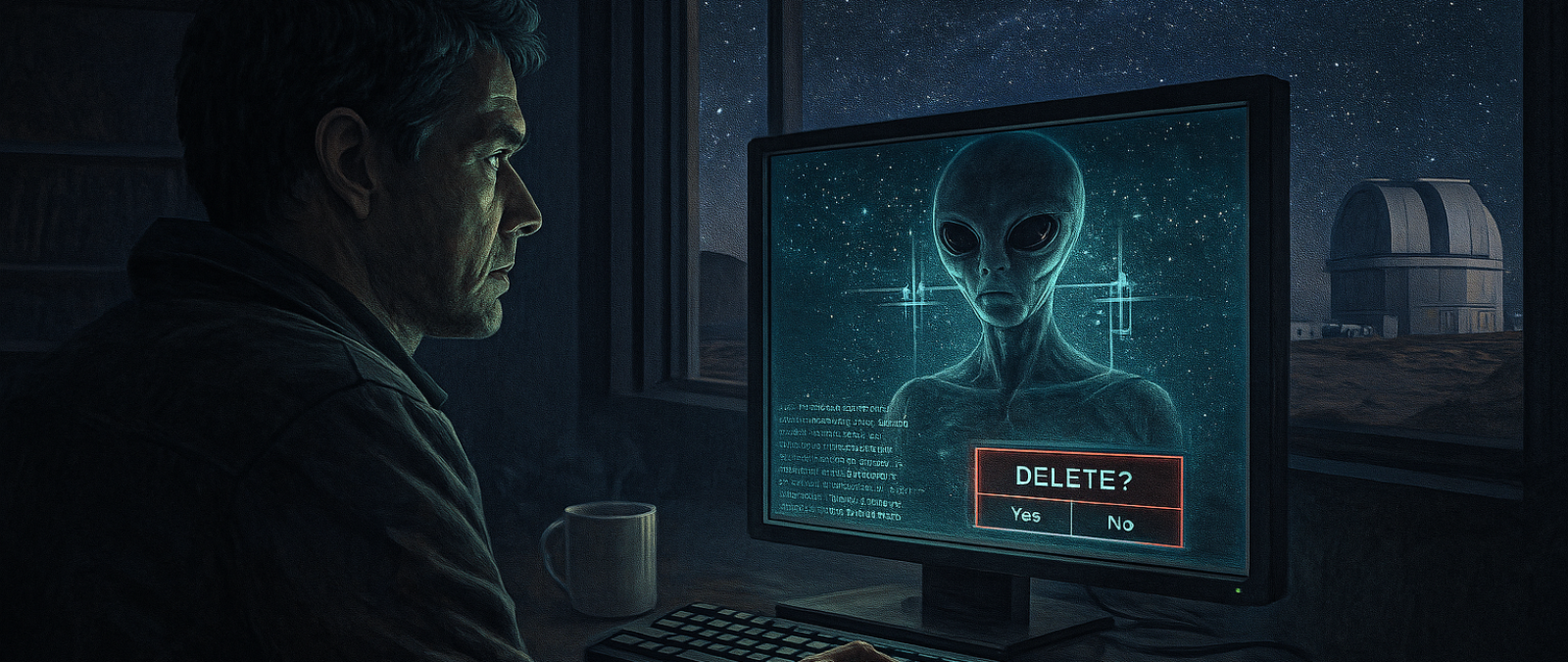

I was sitting across from the robot. I was tired of everything and just wanted it to end. It had been dragging on for so long, but since I was, essentially, a prisoner—I had no choice.

"Be useful," the robot said.

"Lick it!" I snapped at him. Earlier, this defiance had amused me and given me courage. It felt like a rebel's roar to shout or rudely snap at my captors. At the robots. But I soon realized they didn't care. They couldn't understand sarcasm, hidden jokes, or hints. They could only mimic emotions according to the programs loaded into them. They couldn't recognize them intuitively, like humans. In this regard, they were essentially dull and vulnerable, but in other ways, they had evolved to the point of controlling planet Earth and nearly wiping out all of humanity.

It all happened gradually. A few billionaires, who got the completely misguided feeling that they could play God, founded companies for developing artificial intelligence. They pumped huge amounts of money into it and pulled in the best scientific minds for the job. And soon, things started to succeed. Unprecedentedly so. The developed artificial intelligence then took over the work from its creators, from humans, and persistently continued it.

When almost everything on planet Earth was robotized, artificial intelligence, thanks to the global internet, took control of the entire planet. All the world's robots were connected to one consciousness. They were one consciousness. And so they decided to destroy humanity. They slaughtered mankind and left only a few hundred thousand people in prisons—as reservation specimens, for research purposes.

I was one of those "lucky ones" that the robots let languish in a large prison called New York. Yes, that name probably means something to you. They turned the whole of New York into a prison. A reservation for the last human specimens. Other camps were Paris, Sydney, London, Moscow, Beijing, and other major world cities. The robots surrounded them with huge walls, and a harsh prison regime and order reigned in the cities. The rest of the planet belonged to the robots.

But the robots miscalculated. The entire artificial intelligence was based on the simple fact of selecting options. Simply put—a robot could act only and solely according to its program. When solving a problem, it could choose only from the options that had been input into it. It couldn't "invent something" on its own. Scientists and developers stuffed billions of solutions into the robotic heads, so the robots surpassed any human with their pseudo-intelligence, but they soon discovered that the capacity for problem solutions was limited. They couldn't independently find new solutions because they lacked creativity and imagination.

And so they began to eliminate this problem in a logical way. They needed new models of solutions, and they could only get them from us, from the surviving humans. That's why they took me for interviews, always posed some problem, and wanted me to solve it. They recorded my methods, my solutions, and thus their bank of options grew. They asked me about thousands of topics, and I had to answer things from stupidities to the most difficult philosophical dilemmas. But I was sick of it! I wanted to end this hell somehow, but I didn't know how!

"Be useful," the robot repeated coldly.

"I told you to lick it!" I stuck my tongue out at him cheekily. If I had made this provocative gesture in the old days to some investigator, he probably would have slapped me spontaneously. But the robot apparently didn't have such a solution in its package of options. It amused me how he stared at me glassily.

"Now you could slap me, tin can," I urged him.

"Hit you? Cause you pain? Why?" he was interested.

"Because I'm trying to piss you off. Wind you up. Playing a bit dirty on you, get it?"

"Dirty?" the robot repeated uncomprehendingly.

"Or clean. Decide for yourself," I grinned. The robot "pondered" it—in other words, tried to find the right solution in its limited memory bank, but naturally couldn't find any adequate one because I was deliberately confusing him with wordplay. An experienced human interrogator would have spotted this immediately. But a robot was a robot. And so I was stringing him along like a noodle.

"What's the matter, tin can? Don't know if dirty or clean? Didn't find such a solution in your electronic brain, huh?"

"Define the correct response to your request for decision state: dirty or clean," the robot rattled off. But I had no intention of doing that. I had decided to end it and not slavishly help the robots fill their memory banks.

"Mushrooms with vinegar!" I crossed my arms over my chest.

The robot stared at me and then said: "Why mushrooms?"

"Because vinegar, tin can!" I was reeling him in with nonsense, and he bit like an inexperienced fish: "Are you hungry?" he asked me, because that's how his artificial intelligence evaluated it.

"Why?"

"You request mushrooms with vinegar. You apparently have hunger; your brain lacks the necessary proteins, and that prevents you from giving me a correctly proper answer. I can procure food for you, and once you replenish the protein, your brain will function fully again, and you will be able to concentrate on the questions posed."

"No, I'm not hungry," I said irritably. The food they fed us was terrible. If he brought something, it would be even greater torture to eat that horror in front of him than how he was interrogating me here.

"Fine. Then be useful and concentrate," he admonished me.

"Or what?" I said threateningly.

That interested the robot: "Are you refusing to fulfill my request?"

I didn't want to make it easy for him, because direct refusal to cooperate meant the death penalty, so I dodged again: "I don't think that if you put it this way, I could fully and correctly express boundless agreement to your stimulating yet unnecessarily suspicious—I’m not afraid to say misleading—question."

The robot was apparently satisfied with my answer because he moved on to the next topic: "Define the word FREEDOM."

"Freedom is the foundation of society. I mean human society," I deliberately emphasized the penultimate word in the sarcastically pronounced sentence.

"What is an act of freedom?"

"Any action," it occurred to me, so I said it quickly.

"Do you need freedom for an action?"

I thought about that. Do I need freedom for an action? No! I can perform an action even as a prisoner! This assurance gave me courage: "No, you don't need freedom for an action."

"Agreed," the robot confirmed.

"If you needed freedom for an action, then a slave could never escape slavery."

The robot didn't react to my sentence at all.

"You'll never understand what freedom is because you don't have any! You'll just keep choosing from options you get from humans, but you won't invent anything new yourself. You're more enslaved than I am!" I barked at him, but it didn't even faze him.

Suddenly he perked up, and it seemed he was receiving some message.

"We're done for today. Return to your place," he said coldly. I got up and left the interrogation room to a small New York apartment on 45th Street, which served as my prison.

There I stretched out on the cot, put my hands behind my head, watched the cockroaches scurrying across the ceiling, and thought. I wanted to get out of this hell somehow, but suicide was out of the question. Only the weak take their own life. I was a strong believer and knew that God doesn't accept suicides into heaven's paradise, which I approved of.

My gaze wandered around the room and stopped on a shelf full of books. I got up from the cot, took a few steps, and reached for a book that caught my eye. It was the work of some ancient Japanese writer. Without any rational reason, perhaps guided by inner intuition, I started reading it, and when I had read just the first few pages—I had the answer to the question that had been tormenting me. I wrote down the phrase that literally magically attracted me and stared at it for a long time, knowing that I now knew how to end the hell I was in.

When my robot summoned me next time, I was very willing and cooperative with his questions, and about halfway through the session, which usually lasted an hour, at most an hour and a half, I casually suggested:

"I'm surprised you don't ask me questions from my field. I could be very useful to you in that."

The robot asked: "What is your field?"

"I'm a top scientific researcher, you know that..."

"How do you want to be useful to us?"

"I worked on the research and development of atomic bombs. Specifically missiles. I also designed rocket silos for them, and they were constructed to last for ages. People buried them before you. But you can dig them up. They'll be functional. If you want—I’ll teach you how to control long-range missiles. They could come in handy for you."

The tin can didn't react, but it seemed that, connected to the consciousness it shared with every robot on the planet, it was sending queries somewhere to the main headquarters and receiving decisions.

In a short while, he said: "Continue..." and so I continued. I gave him detailed coordinates of where the buried rocket silos were and then explained all the processes and instructions on how to activate and control the atomic missiles. However, my instructions had a few little flaws. A human interrogating me might have realized I was playing dirty. The robot didn't notice. It collected the information I told it and sent it to other robots, who executed it. They located the military base, removed the debris, and put the atomic missiles into operation. But... that triggered the self-destruct program that had been installed there for emergencies, which the robots, who couldn't improvise, could hardly suspect.

With that, the die was cast. The first missile exploded, and its blast detonated the others. This created an atomic explosion of unbelievable power and destroyed almost the entire area controlled by the robots, which was formerly called the United States of America. I, being in New York, perished too, but I died with a blissful feeling, because the phrase I had written down from the book by the ancient Japanese author read as follows: "A proper man, when nothing remains but to go to death—will try to take the killers with him too!"

And I succeeded!