Press Report:

Recent experiments with living organisms in space — whether aboard the International Space Station or the earlier Soviet Mir station — have brought crucial insights that could redefine our plans for interstellar colonization. It has been found that gravity is not merely a force but a fundamental evolutionary stimulus, without which biological organisms cannot properly develop.

This raises a vital question for humanity: What would happen to people born and raised on a planet with different gravity — for example, Mars, where the pull is only 38% of Earth’s? Would they still be like us?

From the sky came something that was neither thunder nor an airplane. It was a deep, tearing roar rolling from the clouds like an avalanche, followed by a whistling chain of fiery spheres. In a remote corner of Canada, far from city lights, an object fell from the clouds, burying itself deep into a field, leaving behind a trail of smoke and the smell of burnt metal and ozone.

The first to arrive were two farmers on their early shift. They stood at the edge of the smoking crater, unable to believe their eyes. In the middle lay half of an ellipsoid capsule, resembling a strange seed that had failed to sprout. When they finally dared to come closer, they found inside a glass cockpit a being that looked human — but small and fragile, like a hatchling. It was a boy, a child. His body was battered and weak, but he was breathing.

He was immediately taken to the nearest hospital, under the care of the experienced Dr. Miley Broos, known for her calm mind and open heart. It was she who noticed that, though the boy’s body was injured, there were no burn marks. He was simply bruised.

A few hours later, when the boy regained consciousness, he looked at the doctor with a bewildered expression, as if trying to understand where he was.

“My name is Elian,” he whispered, his voice chiming like small bells. “And I am a refugee.”

Dr. Broos smiled gently. “A refugee, I see. But from where?”

Elian hesitated for a moment.

“I’m from Mars,” he said, his tone completely flat. “I escaped from the Great Symmetry.”

Dr. Broos looked at him kindly, then asked with quiet compassion, “Why did you escape?”

“I wasn’t symmetrical enough,” Elian whispered. There was no fear in his voice — only a deep, inner sorrow. “They want to unify the universe. They say it’s their purpose, and that every being must work toward it. But I didn’t want that. I wanted to build a ship — not to serve, but for joy. And that, to them, is unthinkable. I ran away because I discovered something inside me they call heresy — an individual mind.”

Dr. Broos realized she was holding something far greater than a strange, lost child. In her hands lay the key to an entirely different civilization.

Miley watched little Elian as he tried to lift a cup of water. It wasn’t heavy — just a simple ceramic mug — yet for his body, it was an unbearable burden. His hands trembled, the veins on his wrists stood out like blue threads, and he had to lean on the table to keep from falling.

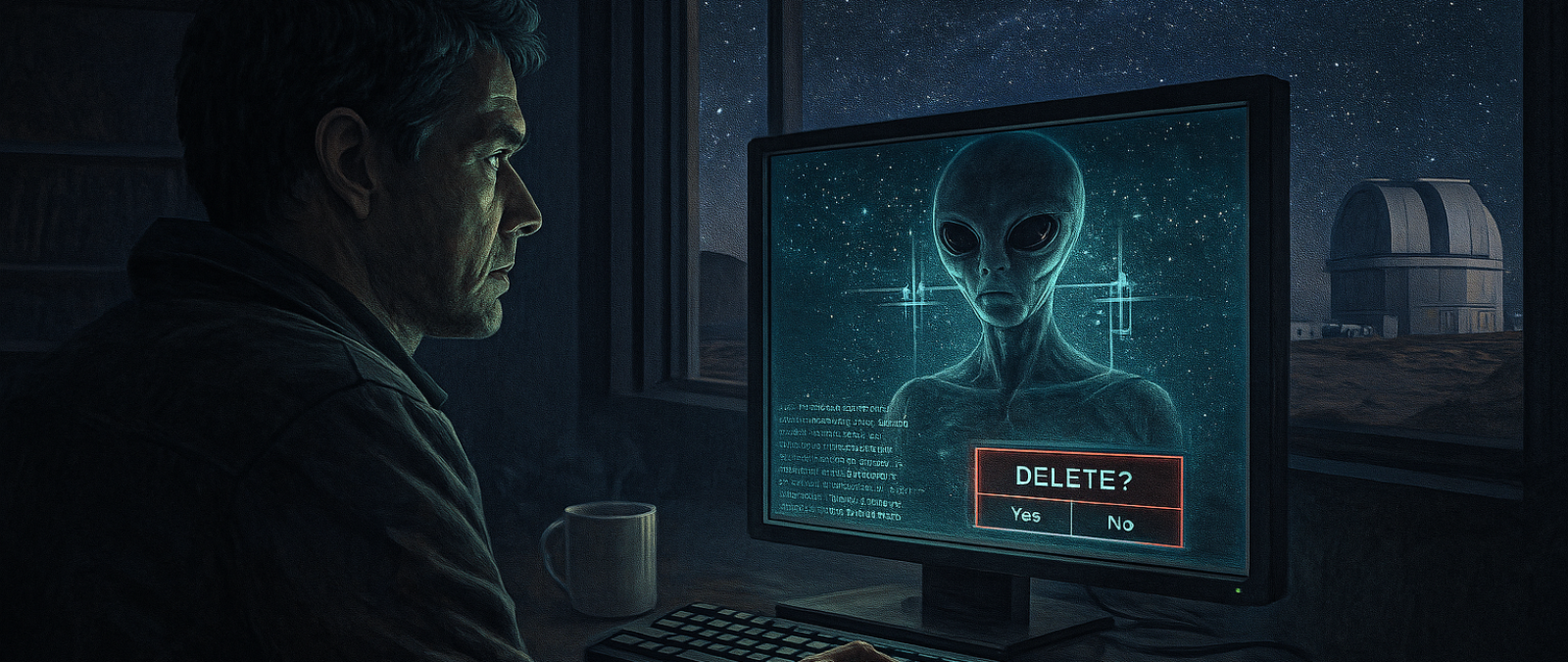

Dr. Broos, with her background in both medicine and research, took notes on her tablet. She understood exactly what was happening.

Elian’s bones were the result of life on a planet with only 38% of Earth’s gravity. His skeleton had never developed under constant pressure, making it porous and light — like the hollow bones of birds, built for flight but not for weight. On Earth, his spine and legs had to withstand forces they were never meant to bear. Miley noted that his femurs, the strongest bones in human anatomy, showed density comparable to that of an elderly woman with advanced osteoporosis. Each step for him was like walking with a backpack full of stones.

His muscles were shaped by the same environment. On Mars, minimal effort was enough to move. His muscle fibers were thinner and less dense, lacking the intricate network of capillaries that nourish them with oxygen. Miley imagined his muscles more like fine threads than Earth’s solid cords — which was why lifting a cup felt to him like lifting a heavy barbell.

But Elian’s greatest struggle was internal. His vestibular system — the delicate mechanism in the inner ear that controls balance — had been perfectly attuned to Martian gravity. The tiny calcium carbonate crystals that sense motion and weight had gone haywire on Earth. Under triple the familiar force, they sent his brain a constant stream of confusing signals. Every movement of his head, every step, every glance made him dizzy and sick. His brain simply couldn’t comprehend why everything had suddenly become so heavy — and why the world seemed to spin.

“He’s not injured,” Miley told her assistant as she watched Elian slowly crossing the room with the help of a robotic walker. “He’s just a Martian. It’s not something exercise or medication can fix. It’s a fundamental biological difference. A body that evolved on Mars simply cannot function properly on Earth. He’s like a fish in air, or a bird underwater. Earth’s gravity isn’t home to him — it’s an alien, hostile force.”

The perfection of Elian’s body — crafted for Mars — became his greatest curse on Earth. Days passed in an exhausting battle with gravity. The robotic walker gave him only the illusion of freedom. In Dr. Broos’s lab, he became both a subject of study and a quiet, lonely witness to a human life he could never live.

Doctors, physiotherapists, and specialists tried everything. Strength exercises drained him completely, and his minimalist body resisted adaptation. His brain never managed to recalibrate his sense of balance. He felt like a true prisoner of Earth’s gravity — and in a tragic way, that’s exactly what he was.

“It’s like trying to grow a tree in the ocean,” Miley said to her team. “You can support it, but it will never truly stand.”

And so the people studying Elian realized that the solution wasn’t to adapt him to Earth — but to adapt Earth to him.

Week by week, they prepared an ambitious project, carefully hidden from the public eye. They called it Refugee. Instead of treating Elian, they would give him a home — a small, self-sustaining community where gravity would be reduced to Martian levels. It would be a glass bubble in the middle of Earth’s wilderness — his home, shielding him from the outside world while letting him live freely. It would include a lab, walking space, even an artificial landscape resembling the red Martian terrain he had left behind.

When Elian first stepped into his new bubble, he felt his muscles relax. The heavy weight that had burdened him for so long lifted, and his body straightened. He walked calmly and freely, filled with a joy he had almost forgotten. He could run, jump — and at last, his mind found peace.

He knew he would never walk freely on Earth. He would always be separate from humankind. But he was no longer a prisoner of gravity. The scientists hadn’t managed to adapt his body — but they had saved his soul.

In the quiet of his glass refuge, Elian was no longer a refugee from Mars, but the first Martian citizen of a new world.

A small, independent being who had found a home — on planet Earth — in the endless universe to which he had dared to travel, defying his destiny, in nothing more than a tiny capsule of hope.